- Privatus 6 0 – Automated Privacy Protection Requirements

- Privatus 6 0 – Automated Privacy Protection Systems

- Privatus 6 0 – Automated Privacy Protection Policy

- Privatus 6 0 – Automated Privacy Protection Software

This is the first of a two-part series discussing the privacy and security issues associated with the widespread use of automated vehicle technology. This first post focuses on potential privacy issues, while the second post – coming soon – will address security issues.

Sight protection 5. Bright screen 6. Easy removable 7. 3H hard coating scratch resistant 8. Block blue light Features 1) At 25 degree from either side. Perfect privacy security Tiny carbon filters of patented Micro-louver technology can adjust viewing angle it can be seen distinct. About this Help Guide. This Help Guide is intended for technical professionals whose responsibilities include administration of Kaspersky Security, and support for organizations using Kaspersky Security.

Privatus has been designed from the ground up with simplicity in mind. Built for ease of use, there is nothing to configure, no favourites, no whitelists, no blacklists, no problems! Privatus just works! Privatus removes all tracking cookies, unnecessary cookies, flash cookies, Silverlight, and databases from your Mac, automatically. Have privacy protection password on my phone, have followed your steps to download the firmware. Have done all that, clicked on format + download, then download, have plugged via USB but I don't see the firmware downloading, all I see is a battery symbol. Network protection: The networks and identities are isolated from the Microsoft corporate network. Firewalls limit traffic into the environment from unauthorized locations. Application security: Engineers who build features follow the security development lifecycle. Automated and manual analyses help identify possible vulnerabilities.

Background

As the development and testing of self-driving car technology has progressed, the prospect of privately-owned autonomous vehicles operating on public roads is nearing. Several states have passed laws related to autonomous vehicles, including Nevada, California, Florida, Michigan, and Tennessee. Other states have ordered that government agencies support testing and operations of these vehicles. Industry experts predict that autonomous vehicles will be commercially available within the next five to ten years. A 2016 federal budget proposal, slated to provide nearly $4 billion in funding for testing connected vehicle systems, could accelerate this time frame. In addition, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) set a goal to work with stakeholders to 'accelerate the deployment' of autonomous technologies.

This post will explore some of the privacy issues that should be addressed before these vehicles are fully commercialized.

A. Owner and Passenger Information

Autonomous vehicles may collect and maintain identifying information about the owner or passenger of the vehicle for a variety of purposes, such as to authenticate authorized use, or to customize comfort, safety, and entertainment settings. This information likely will be able to identify owners and passengers and their activities with a high degree of certainty.

Existing U.S. federal privacy legislation is largely inapplicable to autonomous vehicles:

- The federal Drivers' Privacy Protection Act protects motor vehicle records from disclosure by state departments of motor vehicles.

- Although the Electronic Communications Privacy Act ('ECPA') may protect against the interception of the vehicle's electronic communications or access to stored communications by unauthorized third parties, the service provider (or its vendor) providing the communications or storage functionality may be capture and use these communications without violating the law.

- Although the Federal Communications Act ('FCA') requires 'telecommunications carriers' to protect the confidentiality of 'proprietary information' of customers, it is possible that autonomous vehicle manufacturers or their service providers would not be a 'telecommunications carrier' – a classification more typically applied to operators of landline telephone or cellular phone networks.

State law also may not provide much protection. For example, state data breach notification laws typically require notification of a data breach, but do not impose substantive privacy or security protections. Data security laws, such as those in effect in Massachusetts and California, may not currently apply to the types of data collected or used by autonomous vehicles.

B. Location Tracking

Location data is necessarily collected and used in autonomous vehicles for navigation purposes– e.g., destination information, route information, speed, and time travelled. Location features are also used in existing traditional vehicles to remember locations; provide additional information relevant to the trip, such as real-time traffic data and points-of-interest along the planned route; and to set routing preferences, such as avoiding highways or toll roads. Concerns related to this information have been discussed by politicians and the media, alike.

Sensitive Location Data & Risk of Harm

This post will explore some of the privacy issues that should be addressed before these vehicles are fully commercialized.

A. Owner and Passenger Information

Autonomous vehicles may collect and maintain identifying information about the owner or passenger of the vehicle for a variety of purposes, such as to authenticate authorized use, or to customize comfort, safety, and entertainment settings. This information likely will be able to identify owners and passengers and their activities with a high degree of certainty.

Existing U.S. federal privacy legislation is largely inapplicable to autonomous vehicles:

- The federal Drivers' Privacy Protection Act protects motor vehicle records from disclosure by state departments of motor vehicles.

- Although the Electronic Communications Privacy Act ('ECPA') may protect against the interception of the vehicle's electronic communications or access to stored communications by unauthorized third parties, the service provider (or its vendor) providing the communications or storage functionality may be capture and use these communications without violating the law.

- Although the Federal Communications Act ('FCA') requires 'telecommunications carriers' to protect the confidentiality of 'proprietary information' of customers, it is possible that autonomous vehicle manufacturers or their service providers would not be a 'telecommunications carrier' – a classification more typically applied to operators of landline telephone or cellular phone networks.

State law also may not provide much protection. For example, state data breach notification laws typically require notification of a data breach, but do not impose substantive privacy or security protections. Data security laws, such as those in effect in Massachusetts and California, may not currently apply to the types of data collected or used by autonomous vehicles.

B. Location Tracking

Location data is necessarily collected and used in autonomous vehicles for navigation purposes– e.g., destination information, route information, speed, and time travelled. Location features are also used in existing traditional vehicles to remember locations; provide additional information relevant to the trip, such as real-time traffic data and points-of-interest along the planned route; and to set routing preferences, such as avoiding highways or toll roads. Concerns related to this information have been discussed by politicians and the media, alike.

Sensitive Location Data & Risk of Harm

A data set that correlates location and travel data (e.g., current location, destination, speed, route, date and time) with additional information about the owner and passenger, could provide various benefits. For example, this type of data set may help in traffic planning, reducing congestion, and improving safety. However, this type of combined data set may also reveal sensitive information about individuals, particularly if this information is maintained over time.

These privacy concerns exist both at the individual and societal level. The Supreme Court has already recognized in U.S. v. Jones that location information 'generates a precise, comprehensive record of a person's public movements that reflects a wealth of detail about her familial, political, professional, religious, and sexual associations.' The New York Court of Appeals noted that an individual's historical location and destination information would reveal 'indisputably private' trips, such as to a psychiatrist, plastic surgeon, abortion clinic, AIDS treatment center, strip club, criminal defense attorney, by-the-hour motel, union meeting, place of worship, and gay bar. Aside from the revelation of private information, information about one's present location or travel patterns may create a risk of physical harm or stalking if that information fell into the wrong hands.

Marketing

Location data, when combined with personal information, could also be used for secondary marketing purposes. For instance, a data set combining passenger information with details about the passenger's location may enable a marketer to deduce information about where passengers live, work, shop, and eat. This information may also allow a business to infer information about income level and spending habits. These general types of practices are already common on the internet – companies like Nickelodeon, Google and Facebook have all faced lawsuits related to behavioral tracking using cookies. Other uses of this data may include providing in-vehicle customized advertising (e.g., on a dedicated screen, on mobile devices inside the car, or through car speakers), or routing a vehicle to expose passengers to certain businesses that may be of interest, based on inferences drawn from a passenger's individual data.

Societal Concerns

A fundamental question is how the collection and sharing of location data impacts the concept of an individual's 'reasonable expectation of privacy,' which in turn impacts both protections afforded by the Fourth Amendment. For instance, the Supreme Court held in U.S. v. Jones, that the Government's warrantless attachment of a GPS device to a vehicle violated the Fourth Amendment because the defendant had a reasonable expectation of privacy against such intrusion. However, it remains to be seen how courts will treat governmental use of location data from autonomous vehicles, if the Government is not involved in the installation of tracking technology. Indeed, under the 'third-party doctrine,' which states that an individual has no reasonable expectation of privacy in information voluntarily disclosed to third parties. Justice Sotomayor has recognized that this doctrine may be 'ill suited to the digital age, in which people reveal a great deal of information about themselves to third parties in the course of carrying out mundane tasks.'

C. Sensor Data

Autonomous vehicles (and existing human-driven vehicles) contain sensors that collect data about the vehicle's operation and its surroundings. For example, sensors in Google's self-driving car include cameras, radar, thermal imaging devices, and light detection and ranging (LIDAR) devices that collect data about the environment outside the vehicle. Among other uses, this data helps autonomous vehicles determine the objects it encounters, make predictions about the environment, and take action based on these predictions.

Companies that continuously collect data about a vehicle's surroundings may wish to bear in mind lessons from past enforcement actions. For instance, in 2012, the FCC sanctioned Google for gathering Wi-Fi network information and the content of data transmitted over Wi-Fi networks (including sensitive information, such as email content, websites visited, and passwords) as its Google Street View vehicles gathered images of public roads. Autonomous vehicles are capable of collecting driving habits, destinations and other revealing information about other drivers without their knowledge or consent. Additional concerns could arise based on the use of imagery captured by the vehicle, including ownership disputes and potential invasion of privacy claims, depending upon the circumstances in which the images are captured. Thus, companies engaging in broad data collection may wish to implement safeguards to protect individual privacy.

Voice Recognition and Control

One 'sensor' that deserves particular attention is the voice recognition and control system of the autonomous vehicle. Consumer devices using this type of technology have caused public concern and complaints about the collection and transmission of private communications, and state legislatures have begun to respond. For instance, in October 2015, California enacted legislation regulating voice recognition technology in smart televisions. The California law requires manufacturers to inform customers about the voice-recognition features during initial setup or installation, bars the sale or use of any captured speech for advertising purposes, and prohibits the government from compelling the manufacturer or other relevant parties to build specific features for the purpose of aiding law enforcement authorities. By their own terms, these smart television laws would not apply to autonomous vehicles, but they may foreshadow the types of requirements and restrictions that future legislation may impose.

Voice recording technology may also implicate state and federal laws regarding wire-tapping and consent for recording communications. As discussed above, ECPA is unlikely to offer extensive protection in the context of autonomous vehicles because recording and interception is not prohibited by parties to the communication or service providers, or to the extent that prior consent by one party to the communication has been provided. However, certain state laws that require consent from all parties may create liability for recording the voice of an individual who is not aware of the recording.

D. Third-Party Collection and Use of Data

In 2014, Jim Farley, the Global Vice-President of Marketing and Sales at Ford, told attendees of the Consumer Electronics Show: 'We know everyone who breaks the law, we know when you're doing it. We have GPS in your car, so we know what you're doing. By the way, we don't supply that data to anyone.' Although he later retracted the statement, Farley's comments highlight the privacy implications of data collection and use. Indeed, personal information about an autonomous vehicle user's locations and on-road behavior may be valuable to various government and private sector entities including law enforcement, news media, private investigators, and insurance companies.

From a law enforcement perspective, permitting access to sensor data presents many of the same privacy concerns as devices like traffic cameras, including the ability to track an individual's location or, as suggested by Farley's comments, the ability to identify when individuals may have violated traffic or other laws.

Additionally, sensor data may provide important information to insurance companies. For example, insurers could monitor driving habits and adjust premiums, similar to a voluntary program currently offered by one auto insurer. Insurers may also be interested in leveraging both internal sensors (e.g., those that track speed and bearing of the vehicle) and external sensors (e.g., cameras or LIDAR) in connection with accident investigations. The issue of ownership of this data may impact whether the insurer has a right to acquire or use this data.

Autonomous vehicles also present challenging questions related to another insurance consideration—liability. Various commentators have identified many of these legal issues, including whether the driver, manufacturer or software would be held liable in the event of a collision. Further discussion of these liability issues can be found in the Products Liability Section of the Norton Rose Fulbright White Paper.

E. Addressing Privacy Concerns in Autonomous Vehicles

A variety of measures may be employed to help protect personal information collected and stored by autonomous vehicles. For example:

Legislation

Congress and state legislatures could pass laws to provide protection for autonomous vehicle data, similar to the federal and state laws that protect Event Data Recorder (EDR) data. For example, the federal Driver Privacy Act of 2015 provides that information collected by EDRs belongs to the owner or lessee of the vehicle and restricts data retrieval from EDRs. Seventeen states have enacted statutes to provide protections for EDR data. Generally, under these laws, EDR data may be downloaded only with the consent of the vehicle owner, subject to certain exceptions (e.g., court orders, vehicle safety research, or to service or repair the vehicle).

Anonymization

Data from autonomous vehicles could be anonymized, but steps should be taken to ensure that data reasonably cannot be re-identified, taking into account technological developments, and regulatory guidance. For example, extrapolating from the FTC's apparent view that a unique mobile device identifier or IP address is 'individually-identifiable information,' a unique identifier associated with a vehicle could also be considered personally identifiable, even if an owner or passenger could not always be positively identified.

Privacy by Design

Under a 'privacy by design' approach endorsed by the FTC, companies are encouraged to 'build security into their devices at the outset, rather than as an afterthought and to consider: (1) conducting a privacy or security risk assessment; (2) minimizing the data they collect and retain; and (3) testing their security measures before launching their products.'

Industry Guidance

Companies involved in the development of autonomous vehicles may also take advantage of other industry resources. For example, the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers and the Association of Global Automakers have developed voluntary Consumer Privacy Protection Principles that provide an approach to customer privacy in the development of automobiles and features utilizing innovative technologies.

Notice and Consent

Notice and consent (choice) are key principles under the fair information practice principles, which serve as the foundation of many privacy laws and frameworks. In traditional settings, such as on websites and mobile apps, notice and consent can be provided and obtained via a privacy notice, pop-up messages, buttons, and checkboxes. However, providing notice and obtaining consent may be difficult or unwieldy when a vehicle may continuously collect information in a manner that may not be apparent to the user.

The FTC has been mindful of these types of challenges, and recognizes that choice is not needed for every instance of data collection, particularly when data use is 'generally consistent with consumers' reasonable expectations,' the cost of providing notice and choice outweighs the benefits, or a company de-identifies data it collects 'immediately and effectively.' However, in the context of new technology, it may be difficult to determine a consumer's reasonable expectations.

Providing notice may also pose a challenge in an environment where there is not a clear method of doing so. Iina 1 0 1 – modern video player gratis. The FTC has also recognized and acknowledged these challenges in a Staff Report on the internet of things. FTC suggestions for providing notice include developing video tutorials, affixing QR codes on devices, and providing choices at point of sale, within set-up wizards, or in a 'privacy dashboard.' Not all of these recommendations will necessarily be viable in the context of autonomous vehicles, which pose their own unique challenges. For example, if notice and choice is provided only at the point of sale, a subsequent purchaser in a private sale may not receive effective notice. Providing privacy information in a user manual may also conflict with FTC guidance that the privacy choices should not be buried in lengthy documents. Furthermore, even if notice is effectively provided to the vehicle owner, passengers may still not receive effective notice. Autonomous vehicle designers, developers and manufacturers, may wish to keep these concerns in mind during product development.

Further Reading

For a discussion of the security issues related to privacy cars, please visit the second post in this two-part series, coming soon. For readers seeking more information on additional legal issues affecting autonomous vehicle technology, Norton Rose Fulbright's White Paper includes discussions of regulatory issues, product liability implications and intellectual property issues in the United States and Germany.

To subscribe for updates from our Data Protection Report blog, visit the email sign-up page.

Privatus

Privatus

Privatus 6 0 – Automated Privacy Protection Requirements

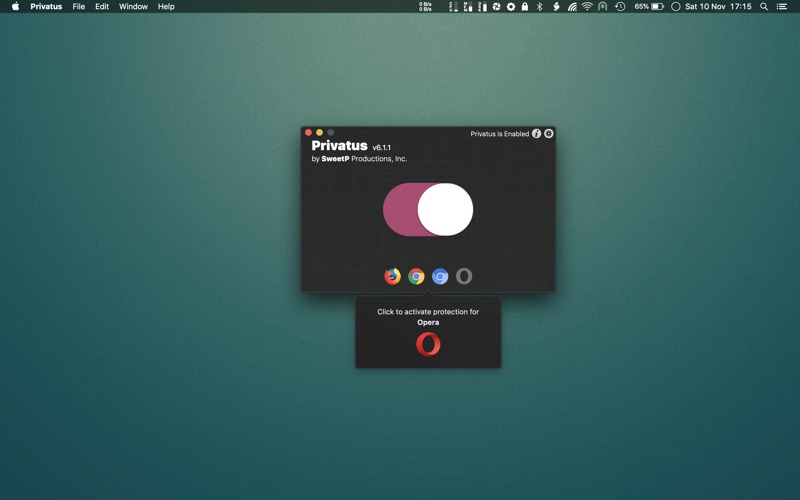

Privatus has been designed from the ground up with simplicity in mind. After a quick initial setup, Privatus will take care of clearing your personal and private browsing tracks automatically after each browsing session.

App has been designed from the ground up with simplicity in mind. After a quick initial setup, App will take care of clearing your personal and private browsing tracks automatically after each browsing session.

Privatus just works!

It has been designed for macOS Sierra, and takes the headaches out of cookie management, freeing your time to be more productive.

Clearing your cookies and cache can have the added benefit of speeding up your browsing experience. Unlike many other Cookie managers, App won't delete your Browser Extensions!

App supports all the major Mac OS X browsers: Safari, Firefox, Chrome, Chromium, and Opera.

Features:

Privatus 6 0 – Automated Privacy Protection Systems

- Automated Cookie, Flash Cookie, Silverlight, Local Storage, Database, Cache, History, Favicons, Webpage previews, Form values and Downloads removal

- One time setup, and forget

- Accessible from the system menu bar

- Highly intuitive

Also recommended to you Deskshare My Screen Recorder Pro

Privatus 6 0 – Automated Privacy Protection Policy

Screenshots:

Privatus 6 0 – Automated Privacy Protection Software

(6.4 Mb)